Creating a laboratory environment in the kitchen is one of the most effective ways to spark a lifelong interest in science. While many simple science experiments appear to be magic tricks, they are actually governed by precise chemical laws and molecular interactions. Moving children from a state of wonder to one of scientific reasoning requires a structured approach to these household activities. By engaging in hands-on chemistry experiments, kids learn to observe, hypothesize, and conclude, mirroring the work of professional scientists.

Key Takeaways for Home Chemistry

Success in home-based science begins with preparation. Before starting any experiment, it is vital to establish a clear workspace and a mindset focused on discovery rather than just the final result.

Safety Precautions for Kitchen Science

Safety must be integrated into the planning phase of every activity. Even when using common household items, the potential for minor accidents exists. Implementing a structured risk management system like the RAMP framework (Recognize, Assess, Minimize, Prepare) is highly recommended.

| Equipment | Standard Requirement | Justification |

| Splash Goggles | Wrap-around style | Protects eyes from pressure bursts or splashes |

| Gloves | Nitrile or latex | Prevents skin irritation from peroxide or dyes |

| Clothing | Cotton apron or smock | Cotton is less reactive to heat than synthetics |

| Footwear | Closed-toe shoes | Protects against dropped glassware or spills |

A critical rule for any home lab is to never mix store-bought chemical cleaners. Combining bleach with vinegar, for example, produces toxic chlorine gas. Always ensure the workspace is well-ventilated and cleared of food or drink to prevent cross-contamination.

Essential Household Supplies Checklist

Most chemistry experiments for kids can be performed using a standard set of ingredients. Keeping these items in a dedicated “science box” makes it easier to conduct an experiment whenever curiosity strikes:

- Baking soda (Sodium bicarbonate)

- White vinegar (Acetic acid)

- Dish soap (acts as a surfactant)

- Hydrogen peroxide (3% or 6% concentration)

- Food coloring (for visual tracking of reactions)

- Empty plastic bottles and clear jars

- Measuring spoons and funnels

Defining Chemical Reactions

Before diving into the procedures, it is helpful to clarify what a chemical reaction actually is. In simple terms, it is a process where substances transform into entirely new substances with different properties.

Signs of Chemical Change

You can often tell a chemical reaction is happening by looking for specific clues. These indicators suggest that bonds between molecules are breaking and reforming:

- Color changes that cannot be explained by simple mixing.

- Temperature shifts (the container gets warmer or cooler).

- The production of gas (bubbles, fizzing, or foam).

- The formation of a precipitate (a solid appearing in a liquid).

- Light or odor being produced.

Chemical Change vs. Physical Change

It is important to distinguish between a chemical change and a physical change. A physical change, such as ice melting into water, changes the state of the matter but not its identity. You can freeze the water back into ice. A chemical change is usually permanent. For example, once you bake a cake, you cannot turn it back into flour and eggs.

Role of Atoms and Molecules

Everything is made of tiny building blocks called atoms. During a chemical reaction, these atoms are rearranged. No atoms are created or destroyed; they simply find new partners to bond with. This concept, known as the Law of Conservation of Mass, ensures that the weight of your starting ingredients equals the weight of your final products, even if some of that mass has turned into invisible gas.

The Efficacy of Active Learning Models

The transition from passive observation to active experimentation represents a significant paradigm shift in early childhood development. In the modern educational landscape of 2024–2026, scientific literacy is increasingly viewed as a core literacy. Empirical evidence underscores the profound impact of active learning on student outcomes. In contrast to traditional lecture-based formats, active learning—where students engage in problem-solving and direct experimentation—has been shown to bridge achievement gaps and enhance long-term retention.

According to research on active learning interventions, students participating in hands-on environments are significantly more likely to succeed than those in passive settings. The following table highlights the quantitative differences in engagement and performance observed in recent educational studies:

| Metric | Active Learning Environment | Passive (Traditional) Environment |

| Mean Examination Scores | 6% Increase (Approx. 0.47 SD) | Baseline |

| Student Percentile Rank | 68th Percentile | 50th Percentile |

| Average Failure Rate | 21.8% | 33.8% |

| Failure Probability | Baseline | 1.5x More Likely |

These statistics demonstrate that the “doing” of science is more effective than the “hearing” of science. Active learning environments foster a reduction in achievement gaps for underrepresented students, suggesting that home-based experiments can serve as a critical tool for educational equity.

Acid-Base Chemical Reactions

The cornerstone of home chemistry is the acid-base reaction. This interaction involves a proton donor (the acid) and a proton acceptor (the base). When they meet, they work to neutralize each other, often creating exciting visual results.

Erupting Baking Soda and Vinegar Volcano

This classic experiment utilizes acetic acid (vinegar) and sodium bicarbonate (baking soda). The reaction happens in two stages: first, a double displacement occurs to form carbonic acid, which then quickly decomposes into water and carbon dioxide gas.

- How to do it: Place baking soda in a container. Add a few drops of dish soap and red food coloring. Pour in vinegar and watch the “lava” flow.

- Why it works: The rapid production of carbon dioxide gas creates the bubbles that push the liquid out of the container.

Lemon Juice Battery Power

Chemistry can also produce electricity. By using the citric acid in a lemon as an electrolyte, you can create a simple battery.

- How to do it: Insert a galvanized nail (zinc) and a copper coin into a lemon. Connect them with a small LED bulb using copper wires.

- Why it works: A chemical reaction between the metals and the acid allows electrons to flow, creating a small electric current.

Fizzy Lemon Suds Experiment

Similar to the volcano, this uses the citric acid found directly in fruit.

- How to do it: Cut a lemon in half and poke the insides with a craft stick to release the juice. Pour baking soda and dish soap over the top.

- Why it works: The citric acid reacts with the base to create a slow-moving, colorful foam.

Red Cabbage Natural pH Indicator

This experiment utilizes anthocyanin, a pigment in red cabbage that changes color depending on the acidity of its environment.

- How to do it: Soak chopped red cabbage in boiling water to create a purple liquid. Distribute the liquid into cups and add different household items like lemon juice (acid) or soapy water (base).

- Why it works: The indicator turns red/pink in acids and green/yellow in bases.

Gas-Producing Chemical Reactions

Gas production is a hallmark of many science experiments for kids. Capturing this gas allows you to see the “invisible” force created by chemical change.

Seltzer Balloon Inflation

You can use a chemical reaction to blow up a balloon without using your breath.

- How to do it: Pour vinegar into a plastic bottle and put baking soda inside a balloon. Stretch the balloon over the bottle neck and lift it to drop the powder inside.

- Why it works: The carbon dioxide gas trapped inside the bottle has nowhere to go but up into the balloon.

Exploding Sandwich Bag Science

This demonstrates how gas pressure can build up until a container can no longer hold it.

- How to do it: Mix vinegar and baking soda inside a sealed zip-lock bag. Place it on the ground and step back.

- Why it works: The gas expands, stretching the plastic until the seal or the bag itself pops.

DIY Baking Soda Rocket Launch

By narrowing the exit point for the gas, you can create thrust.

- How to do it: Use a cork to seal a bottle containing vinegar and baking soda. Turn it upside down (using pencils as a stand).

- Why it works: The pressure forces the cork out, launching the bottle into the air.

Elephant Toothpaste Foam Creation

This experiment demonstrates rapid decomposition and the role of a catalyst.

- How to do it: Mix hydrogen peroxide with dish soap in a bottle. In a separate cup, dissolve yeast in warm water. Pour the yeast into the bottle.

- Why it works: An enzyme in the yeast called catalase acts as a catalyst, speeding up the breakdown of peroxide into water and oxygen. The soap traps the oxygen, creating massive foam. This reaction is exothermic, meaning it releases heat.

Color-Changing Chemical Reactions

Visual transformations are the most engaging part of household chemistry. These changes show that the molecular structure of a substance has been altered.

Magic Milk Surface Tension Art

While largely a physical interaction involving surfactants, it teaches kids about how different substances interact.

- How to do it: Add drops of food coloring to a bowl of whole milk. Touch the center with a cotton swab dipped in dish soap.

- Why it works: The soap breaks the surface tension and bonds with the fat molecules in the milk, causing the colors to dance.

Skittles Rainbow Water Diffusion

This experiment demonstrates solubility and how colors can move without mixing immediately.

- How to do it: Arrange Skittles in a circle on a plate and pour warm water into the center.

- Why it works: The sugar coating dissolves and moves toward the center, creating a vibrant rainbow.

Iodine and Starch Disappearing Act

This is a classic “clock reaction” that demonstrates how certain chemicals can hide or reveal others.

- How to do it: Mix starch (like cornstarch water) with iodine. The water turns dark blue. Adding Vitamin C will make the color disappear.

- Why it works: The Vitamin C changes the iodine into a colorless ion.

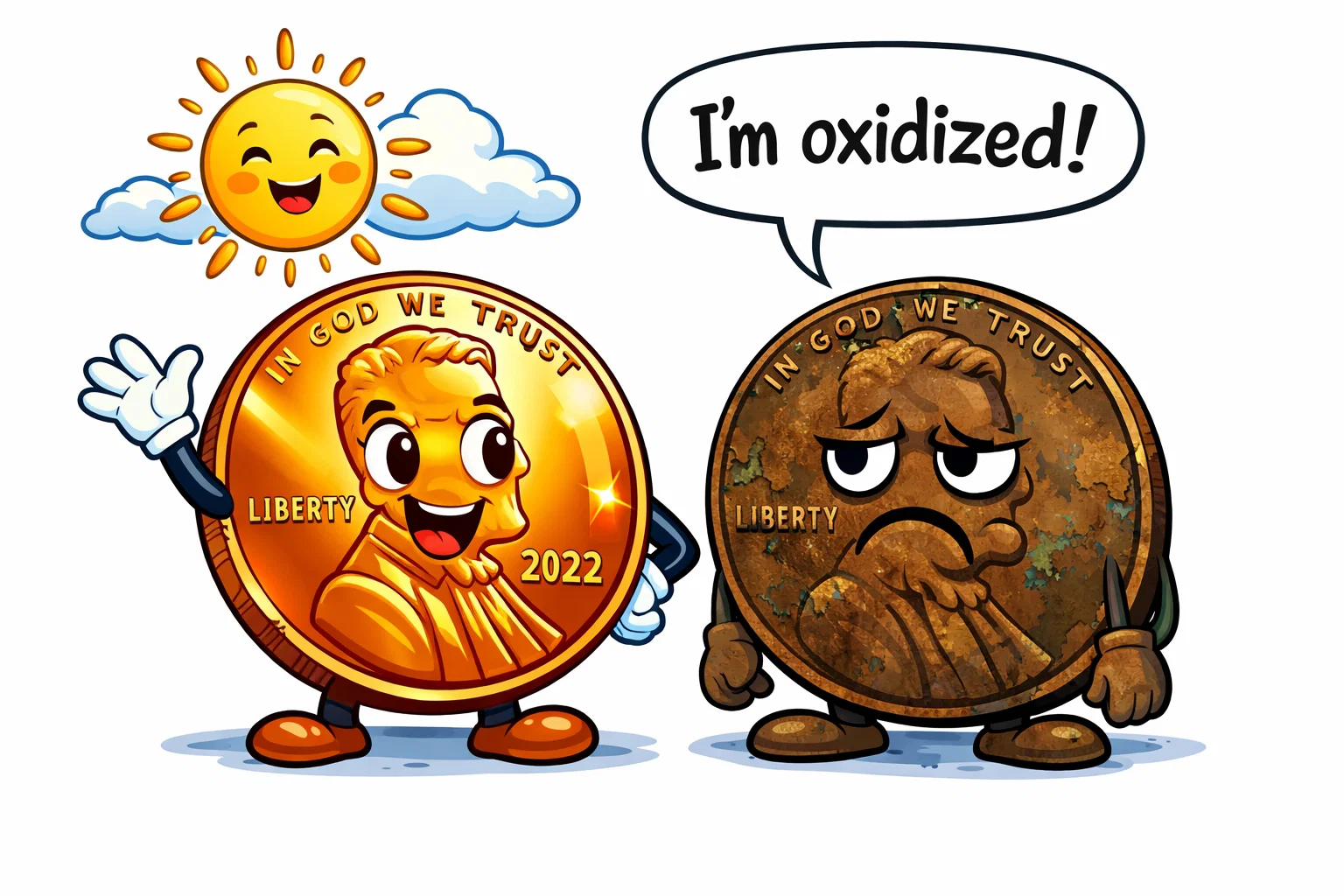

Copper Coin Cleaning Solution

Witness oxidation being reversed using kitchen pantry staples.

- How to do it: Soak dull, brown pennies in a mixture of salt and vinegar.

- Why it works: The acid dissolves the copper oxide layer on the penny, leaving it shiny and new.

Chemical Reactions Creating New Materials

Some reactions result in the creation of polymers or crystals—materials that feel completely different from their original ingredients.

Slime Making Polymer Science

Slime is a favorite chemistry experiment for kids that demonstrates polymerization.

- How to do it: Mix PVA glue with a borax solution or contact lens solution.

- Why it works: The borate ions cross-link the long glue molecules together, turning a liquid into a flexible solid.

Salt Crystals on String Formation

This illustrates how a supersaturated solution can lead to the growth of solid structures.

- How to do it: Dissolve as much salt as possible in hot water. Hang a string into the jar and wait several days.

- Why it works: As the water evaporates, the salt molecules clump together on the string to form crystals.

Invisible Ink Heat Activation

Use chemistry to send secret messages.

- How to do it: Write on paper using lemon juice. Once dry, hold the paper near a heat source (like a lightbulb).

- Why it works: The heat causes the carbon-based compounds in the juice to oxidize and turn brown.

Homemade Ice Cream in Bag

This reaction demonstrates an endothermic process and the freezing point depression of water.

- How to do it: Place milk and sugar in a small bag. Place that bag inside a larger bag filled with ice and a lot of salt. Shake for 10 minutes.

- Why it works: The salt lowers the freezing point of the ice, allowing it to get cold enough to freeze the milk mixture.

Oxidation and Combustion Experiments

Oxidation is a common chemical reaction that occurs all around us, from the rusting of a car to the browning of a sliced apple.

Citrus Candle Burning Process

A candle is a combustion reaction where fuel reacts with oxygen to produce light and heat.

- How to do it: Carefully use the center “wick” of a hollowed-out orange peel filled with vegetable oil.

- Why it works: The oil acts as a fuel that undergoes a chemical change when ignited.

Steel Wool Rusting Observation

Rust is the result of iron reacting with oxygen and moisture.

- How to do it: Soak steel wool in vinegar (to remove the protective coating) and place it in a jar with a thermometer.

- Why it works: As the steel wool oxidizes (rusts), it releases heat, which you can see on the thermometer.

Apple Browning Prevention Test

Stop a chemical reaction before it starts.

- How to do it: Slice an apple and coat one piece in lemon juice, leaving the other plain.

- Why it works: The Vitamin C in the lemon juice acts as an antioxidant, preventing the enzymes in the apple from reacting with the air.

Liquid Density and Viscosity Experiments

While density is a physical property, these experiments often involve chemical interactions to create movement or layers.

Rainbow in Jar Layers

- How to do it: Layer liquids of different densities, such as honey, dish soap, water, and oil.

- Why it works: Heavier molecules sink to the bottom while lighter ones float.

Homemade Lava Lamp Motion

- How to do it: Fill a jar with oil and a little bit of colored water. Drop in an antacid tablet.

- Why it works: The tablet reacts with the water to create carbon dioxide gas, which carries the colored water up through the oil.

Dancing Raisins Carbonation Study

- How to do it: Drop raisins into a glass of clear soda.

- Why it works: Bubbles of carbon dioxide attach to the rough surface of the raisins, acting like tiny life jackets to pull them to the top.

Fireworks in Jar Oil Diffusion

- How to do it: Mix food coloring with oil and pour it into a jar of water.

- Why it works: Since oil is less dense than water, it stays on top. As the heavy food coloring drops out of the oil and into the water, it diffuses like a firework.