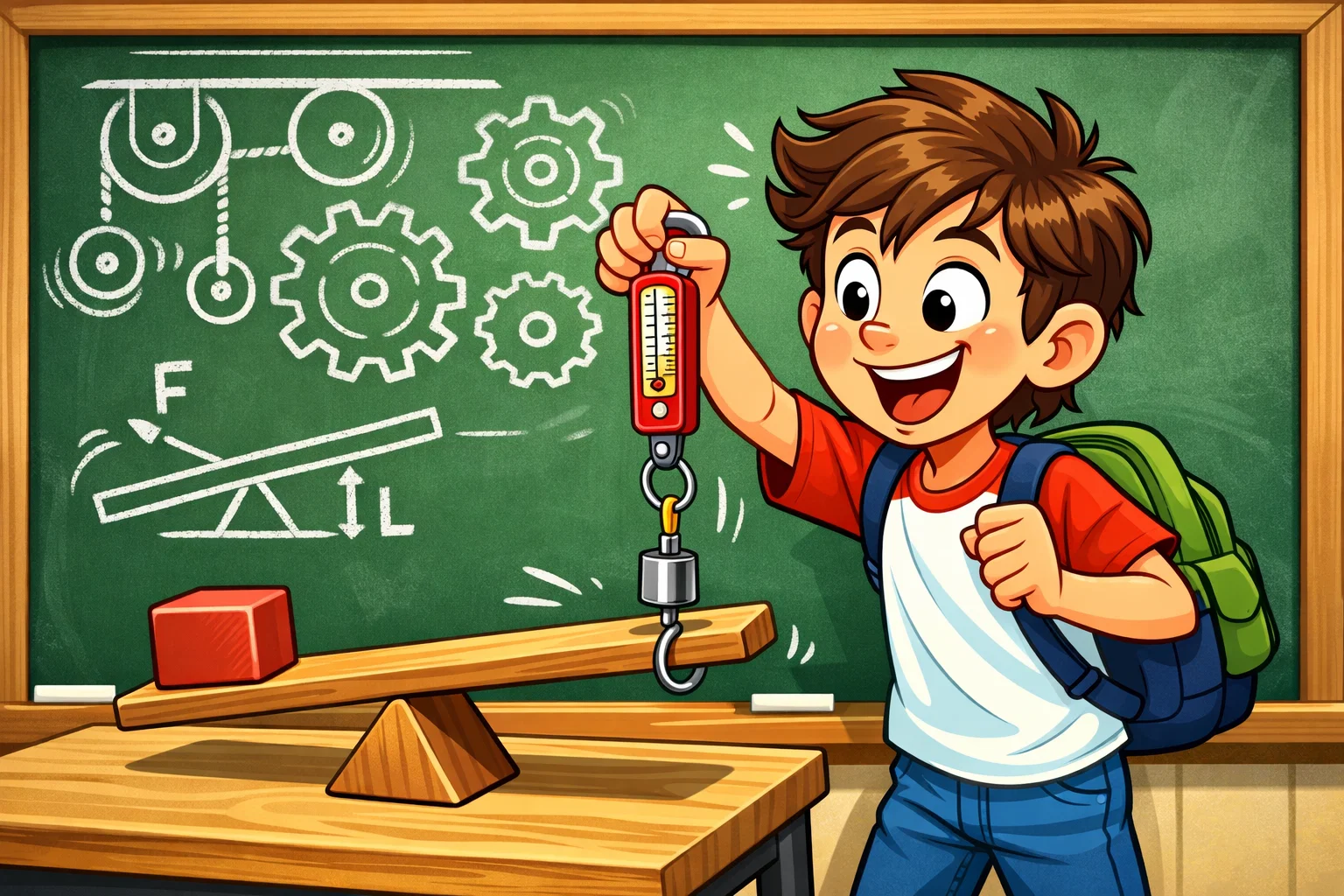

Introducing children to physics begins with the lever, a fundamental intersection of classical mechanics and engineering. As a non-motorized simple machine, it provides mechanical advantage by altering force magnitude or direction.

- STEM Foundation: The lever is a core mechanical tool governed by laws of statics and rotational equilibrium.

- Scientific Core: It consists of a rigid beam pivoting around a fixed point to multiply effort.

Lever Basics: Power of Mechanical Advantage

The efficiency of this system is defined by the Law of the Lever, famously codified by Archimedes of Syracuse. It demonstrates that science provides practical tools for interacting with the physical world through geometric reasoning.

- Archimedes’ Principle: Equilibrium is achieved when distances from the fulcrum are reciprocally proportional to weights.

- System Goal: The primary objective is to obtain mechanical advantage by trading applied force for movement distance.

- Dynamic Transition: When effort torque exceeds load torque, the system shifts from static balance to active movement.

Parts of Lever: Fulcrum, Load, and Effort

Mastering experiments requires identifying three essential components that dictate how the system functions. The fulcrum is the stationary pivot point supporting the beam. The load is the object being moved or the resistance to overcome. Finally, the effort is the input force applied to the system to perform work.

Science Behind Strength: How Levers Work

They mechanics rely on torque, or rotational force. For a system to stay balanced, opposing torques must be equal in magnitude. Rotational force is determined by multiplying force by the distance from the pivot point. A state of equilibrium is reached when (Effort) x (Distance to Effort) equals (Load) x (Distance to Load). Levers transform modest input effort into a significantly more powerful output force.

Mechanical Advantage: Why Levers Make Lifting Easier

Mechanical advantage measures force amplification, describing the trade-off required to achieve a desired output. This occurs when the distance from the fulcrum to the effort point is greater than the distance to the load. While force is multiplied, the total work performed remains constant, meaning effort must be applied over a larger distance.

Educational Research and Cognitive Development

Integrating lever mechanics into education requires understanding cognitive development, particularly Jean Piaget’s Concrete Operational stage (ages 7–11). At this stage, children transition from intuitive thinking to logical reasoning based on tangible objects. Mastering these concepts relies on decentration (considering multiple dimensions simultaneously), reversibility (understanding adjustments can be undone), and conservation (realizing mass and force remain constant despite changes in arrangement).

The current landscape of STEM education shows a critical need for intervention based on recent studies:

- Declining Proficiency: 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data shows a 4-point decline in 8th-grade science scores since 2019.

Three Classes of Levers: Simple Breakdown

Levers are categorized into three distinct classes based on the spatial configuration of the fulcrum, the effort, and the load. This classification system is essential for understanding how different mechanical advantages are achieved in various applications.

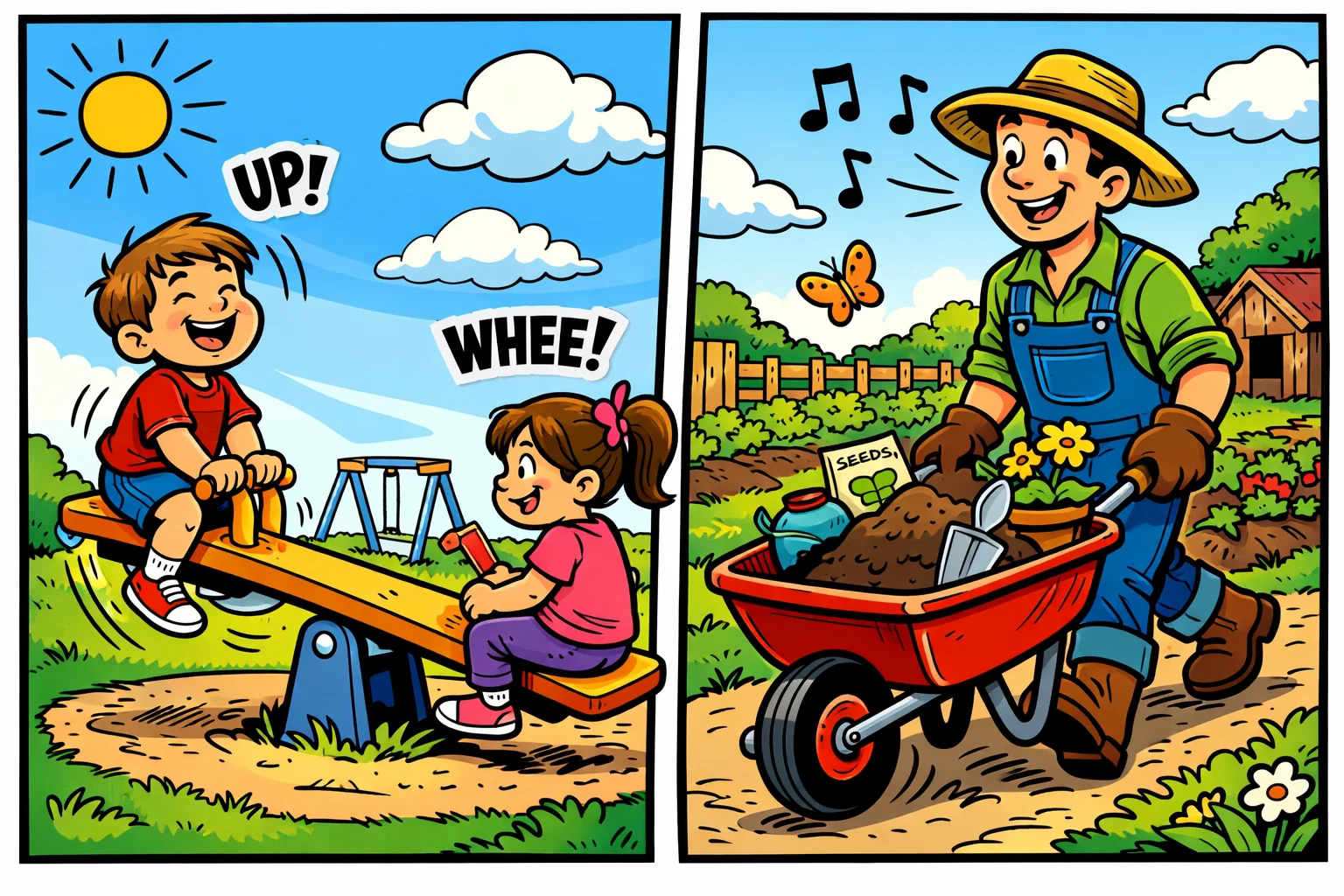

First Class Levers: Seesaw Dynamics

In a first-class lever, the fulcrum is positioned between the effort and the load. The primary mechanical function is directional change and force balance. A classic example is the playground seesaw. Depending on where the pivot is placed, the mechanical advantage can be greater than, equal to, or less than one.

Second Class Levers: Mighty Wheelbarrow Power

Second-class levers place the load between the fulcrum and the effort. Because the effort arm is always longer than the load arm, the mechanical advantage is always greater than one. This makes these levers ideal for force amplification and heavy lifting, such as when using a wheelbarrow to move soil in a garden.

Third Class Levers: Tongs and Tweezers Precision

In a third-class lever, the effort is applied between the fulcrum and the load. Here, the mechanical advantage is always less than one. While it requires more force to move the load, the benefit is increased speed and distance of movement. Tweezers and fishing rods are prime examples of this class.

Double Levers: Complex Simple Machines

Sometimes, two levers work together to perform a task. Scissors and pliers are considered double levers. They consist of two first-class levers joined at a common fulcrum. This configuration allows for both force amplification and the ability to grip or cut materials effectively.

| Lever Class | Fulcrum Position | Effort/Load Placement | Primary Mechanical Function |

| First Class | Between effort and load | Opposite sides of pivot | Directional change and balance |

| Second Class | At one end of beam | Load is in the middle | Force amplification (heavy lifting) |

| Third Class | At one end of beam | Effort is in the middle | Speed and distance of movement |

Hands-On Lever Experiments: Easy Home Activities

To bridge the gap between theory and practice, you can facilitate several activities at home or in the classroom. These experiments turn abstract physics into a tangible science project.

Experiment 1: Classic Seesaw Balance Challenge

Using a rigid 12-inch ruler and a triangular eraser as a fulcrum, ask children to balance different amounts of pennies on either side. Start with an equal number of pennies at equal distances. Then, move one stack closer to the center and observe what happens. This experiment demonstrates the basic requirement for equilibrium.

Experiment 2: Heavy Lifting with Fulcrum Placement

Find a heavy object, like a large book. Place a sturdy ruler under the edge of the book and use a marker as a fulcrum. Experiment with placing the marker very close to the book versus further away. You will notice that the closer the fulcrum is to the load, the easier it is to lift the book.

Experiment 3: Build Your Own Balance Scale

Create a first-class lever by hanging two small cups from either end of a clothes hanger. Use a string to hang the hanger from a doorframe. This balance scale allows kids to compare the weights of various household items, illustrating how levers serve as precise measuring tools.

Experiment 4: Human Body as Lever

The human body is full of levers. Your forearm is a third-class lever. The elbow is the fulcrum, the bicep muscle provides the effort, and the hand holds the load. Have the child lift a small weight and feel their bicep contract. This shows how biological systems utilize mechanical principles for movement.

Experiment 5: Small Levers vs Large Levers

Compare the effectiveness of a short lever versus a long one. Try prying a lid off a container with a short spoon versus a long screwdriver. This activity highlights why increasing the length of the effort arm reduces the force required to move a load.

General Safety Tips for Kids and Parents

Safety management is a non-negotiable parameter for hands-on STEM activities. According to National Science Teaching Association (NSTA) guidelines, a risk assessment should be performed before any demonstration.

- PPE: Wear safety glasses if experiments involve heavy weights or potential mechanical failure.

- Fulcrum Stability: Secure the fulcrum with masking tape to prevent it from rolling or sliding.

- Weight Management: Prohibit “catapulting” weights and keep fingers clear of pinch points.

- Supervision: An adult must be present when using larger models like wooden boards.

Teaching Levers: STEM Lessons for Middle School

For older students, the complexity of the science project can be increased by incorporating measurement and data analysis.

Critical Question: Are Levers Really Helpful?

Challenge students to prove that levers actually save effort. Have them use a spring scale to measure the force required to lift a load directly, then measure the force required when using various lever configurations.

Fulcrum Placement: Does Position Change Difficulty?

By using standardized measurement increments (e.g., 2-cm adjustments), students can create graphs that visualize the relationship between arm length and the force required for lift. This demonstrates the mathematical consistency of physics.

Testing Different Materials: What You Need

Conducting effective experiments requires specific materials. A 24-inch metric wooden ruler is recommended for the beam, while uniform weights like pennies or metal washers ensure precise data.

| Component | Recommended Material | Technical Requirement |

| Lever Beam | 24-inch wooden ruler | Rigid, low-flexibility |

| Fulcrum | PVC pipe or binder clip | Stable, non-rolling |

| Load Weight | Large bar of soap or rocks | High mass, flat surface |

| Effort Unit | Pennies or marbles | Small and uniform |

Results and Observations: What Happened?

In the “Lift the Teacher” case study, students find that a 5th-grade student weighing 80 pounds can lift a 160-pound adult if the teacher stands 1 foot from the pivot and the student pushes down 3 feet away. These demonstrations transform abstract concepts into memorable events.

Everyday Lever Examples: From Playgrounds to Engineering

Observational analysis of levers in daily life provides a powerful mechanism for bridging the gap between physics and reality.

Common Household Levers for Kids

- Nail Puller (Hammer): A first-class lever where the handle provides a long effort arm to pull a stubborn nail.

- Nutcracker: A second-class lever that amplifies force to crack hard shells.

- Broom: A third-class lever where the hand in the middle provides effort to move the bristles quickly across a large area.

Simple Machines in Nature and Anatomy

Beyond human tools, nature utilizes levers. A bird’s wing acts as a lever during flight, and a grasshopper’s legs are designed for explosive force using similar mechanical principles.

Real-Life Engineering: Archimedes Screw and Modern Tools

Archimedes recognized the profound implications of the lever, famously asserting that with a sufficiently long lever and a place to stand, he could move the entire world. This logic is still used in the design of cranes, car jacks, and heavy machinery used in construction today.

Creative Ways to Use Physics Supplies at Home

Encourage children to look for “levers in the wild.” Finding a bottle opener or a pair of scissors and identifying the fulcrum, load, and effort helps solidify their knowledge. This psychological engagement is crucial, as early interest in science is one of the strongest predictors of future professional success in technology-driven industries.