If you have ever watched water climb up a straw or seen a paper towel pull up a spill, you have witnessed one of the most fascinating physical phenomena in nature. For parents and educators, these moments are not just simple cleanup tasks; they are perfect opportunities to spark a child’s interest in science. Engaging in a capillary action experiment allows children to visualize how liquid moves in ways that seem to defy the pull of gravity.

Children are naturally curious about the world around them. Using a hands-on activity to explain complex concepts is far more effective than reading from a textbook. When children see colors “walking” between cups or flowers changing shades overnight, the abstract becomes tangible. These experiments are low-cost, high-impact tools that foster critical thinking and observation skills from a very young age.

Top Capillary Action Experiment Ideas

There are several ways to demonstrate this process using common household items. Each activity offers a unique visual result that highlights how water interacts with different materials.

Walking Water Rainbow Challenge

This classic setup uses jars of water colored with food coloring and folded bridges of paper towel. By placing an empty jar between two full ones, fluid travels up the towel, over the edge, and into the empty container. Over time, the colors mix to create a full rainbow, demonstrating both the movement of molecules and the principles of color theory.

Color Changing Flowers Activity

Using white carnations or stalks of celery, it is possible to show how a plant drinks. When the stem is placed in a cup of water mixed with food coloring, the liquid travels through the internal structures of the stem all the way to the petals or leaves. This clearly illustrates that the action isn’t just a kitchen trick; it is a vital biological function.

Celery Stalk Water Absorption

Similar to the flower activity, celery is excellent for this because the xylem (veins) are very large. After a few hours in colored liquid, cutting the stalk reveals dyed dots. This helps children visualize that water doesn’t just coat the outside; it moves through specific channels inside the plant.

Coffee Filter Chromatography Craft

By using markers to draw a circle on a coffee filter and then dipping the center into water, the liquid spreads outward. As the moisture moves through the fibers of the filter, it carries the ink with it. Because different ink molecules move at different speeds, the colors separate, creating a tie-dye effect that reveals the hidden components of a single marker color.

Growing Rainbow Paper Towel Test

On a strip of paper towel, drawing small rectangles of different colors at both ends and dipping them into water allows the colors to stretch toward the middle. This activity is particularly good for measuring the speed of the liquid as it moves through the porous material.

Self-Assembling Toothpick Stars

Snapping five toothpicks in half (without breaking them fully) and arranging them in a circle so the broken centers meet creates a unique effect. When a small amount of water is dropped into the center, the wood fibers absorb the liquid. As the molecules expand, the toothpicks straighten out, causing them to push against each other and form a perfect star shape.

Visualizing Leaf Veins Science

Placing a fresh, light-colored leaf in a strong solution of food coloring emphasizes the intricate network of “pipelines” in nature. This shows how even the smallest leaves rely on these forces to stay hydrated.

Capillary Action Science Basics

To guide students through these activities, a firm grasp of the underlying physics is essential. The movement observed is the result of specific interactions between water and solid surfaces.

Definition of Capillary Action

In simple terms, this is the spontaneous movement of a liquid through narrow spaces. It occurs when the forces pulling the fluid forward are stronger than the forces holding it back. It is the reason why a sponge can soak up a puddle and why trees can move water from deep roots to high leaves.

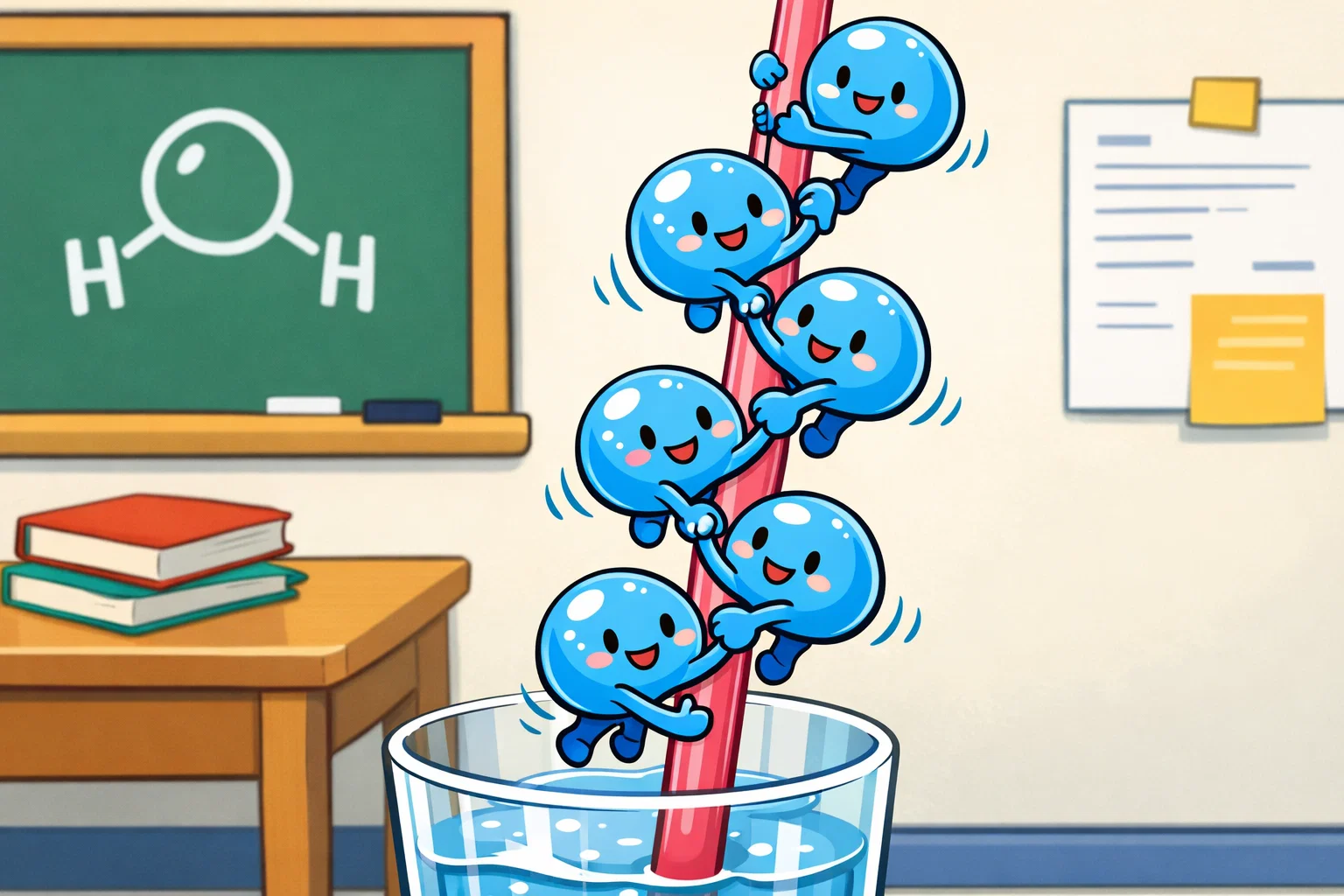

Mechanisms of Cohesion and Adhesion

At the molecular level, two main forces are at work. Cohesion is the attraction between like molecules—in this case, liquid molecules sticking to each other. Adhesion is the attraction between different molecules, such as water sticking to the cellulose in a paper towel. When the adhesive force (the attraction to the container) is stronger than the cohesive force (the liquid’s desire to stay together), the liquid begins to climb.

Science Behind Liquid Movement

While it might look like the water is defying gravity, it is actually following the path of least resistance through tiny channels. As the molecules at the front edge stick to a surface and move forward, they pull the trailing molecules along with them. This creates a continuous chain of molecules that “walks” along the medium.

Capillary Action in Nature

Beyond the kitchen table, this process is essential for life on Earth. Plants use a tissue called xylem, which consists of tiny tubes that act like capillaries. While large trees eventually need a suction force called transpiration (evaporation from leaves) to move liquid hundreds of feet, the initial pull starts with the same principles seen in a paper towel experiment.

Research indicates that engaging in these types of hands-on activities is crucial for long-term academic success. Recent studies on active learning strategies in STEM show that students who participate in experiential learning are significantly more likely to retain information and persist in scientific fields. This is further supported by the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA), which advocates for a “sensemaking” approach. Instead of just memorizing definitions, students should be encouraged to figure out the “why” behind the phenomena they observe.

Step-by-Step STEM Activity Instructions

To ensure the experiment is a success, the following practical guidelines should be followed.

Essential Science Supplies List

| Material | Purpose |

| Clear Jars or Cups | To observe the liquid movement clearly |

| Paper Towel | High-quality brands with high porosity work best |

| Food Coloring | Provides the visual contrast needed to see the “walk” |

| Water | The primary liquid medium |

| Scissors/Knife | For cutting celery or flowers (adult use only) |

Prep Work for Home Experiments

A flat surface should be cleared before starting. Using a tray to catch spills is helpful, as food coloring can stain. Liquid levels should be kept high; the less distance the moisture must climb against gravity, the faster the results will appear.

Safety Guidelines for Young Scientists

While these activities are generally safe, children always require supervision when using food coloring. If a child has sensitivities to dyes, natural alternatives like beet juice can be used. Any cutting of stems must be performed by an adult to prevent injury and to ensure the plant’s xylem isn’t crushed, which would stall the experiment.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Success

- Fill outer jars 3/4 full with water and add 10-20 drops of food coloring.

- Fold the paper towel into a narrow “V” shape to create a dense path for the liquid.

- Place one end of the towel in the colored water and the other in an empty jar.

- Observe the initial wicking. If the fluid stops moving, check for air gaps or evaporation stalls.

Advanced Capillary Action Projects

For older children, more complex variables can be introduced to deepen the inquiry.

Growing Dinosaur Water Expansion

Many “grow-your-own” toys use porous materials that absorb water through capillary action. By measuring the weight and size of the toy over several days, students can calculate the rate of absorption and the total volume of liquid held within the material.

Magic Color Appearance Drawing Book

A “magic” book can be created by drawing on a paper towel with washable markers and hiding the drawing behind another layer of paper. When the bottom edge is dipped in water, the liquid travels up and reveals the hidden colors, demonstrating how moisture moves through multiple layers of a medium simultaneously.

Vertical Liquid Transport Observation

Using different types of materials—like cotton string, newspaper, and sponges—helps identify which can pull water the highest. This introduces Jurin’s Law, which states that the height of the liquid rise is inversely proportional to the width of the tube or pore.

Plant Hydration Simulation

A “self-watering” system for a small potted plant can be designed using a cotton wick. Placing one end in a reservoir of water and the other in the soil demonstrates how the principles of adhesion and cohesion solve practical problems in gardening and agriculture.

Educational Benefits of Play-Based Science

Incorporating these activities into a learning routine offers more than just entertainment; it builds a foundation for long-term education.

Development of Observation Skills

Experiments require children to slow down and look closely. Noticing tiny changes in color and height trains the brain to pay attention to detail—a skill that is vital in all academic disciplines.

Benefits for Preschool and Kindergarten Learners

At this age, the primary goal is “wonder.” Seeing colors mix and water move provides a sensory experience that builds positive associations with science. According to research on early childhood science education, children exposed to scientific inquiry early in life develop stronger problem-solving skills and a more robust vocabulary.

Encouraging Inquiry-Based Exploration

Instead of providing all the answers, asking open-ended questions is more effective: “What might happen if a thicker towel is used?” or “Why did the blue liquid move faster than the red?” This encourages children to form and test hypotheses, which is the heart of the scientific method.