Unlocking the mysteries of Earth doesn’t require a PhD in geology; sometimes all it takes is a curious mind and a few specimens collected from the backyard. Engaging in hands-on activities is a fantastic way to introduce children to the wonders of the natural world through interactive STEM learning. By performing a scratch test, a density test, or even a simple acid test, kids can move from seeing a simple stone to recognizing a rock with a geological history spanning millions of years.

In this guide, we will explore how to set up a home learning unit that covers the rock cycle, mineral identification, and the physical properties of various geological finds. We’ve included instructions for an identification experiment, tips for using a hand lens, and even an edible rock cycle activity to make the science stick. Whether you are a parent looking for fun science at home or a teacher seeking a structured worksheet approach, these activities are designed to make learning about rocks an unforgettable adventure.

Rock Lab Setup for Kids

Creating a “Geology Lab” at home or in the classroom transforms a hobby into a scientific inquiry. The goal isn’t just to label samples, but to develop observation skills and scientific thinking. A designated space—even just a corner of the kitchen table—allows kids to feel like real earth scientists. Encourage them to treat their finds with care, labeling them and keeping a notebook for observations. This structured environment helps children understand that science is a process of gathering evidence to reach a conclusion.

Aims of Rock Lab

The primary objectives of your rock lab should include:

- Developing the ability to categorize samples based on observable properties.

- Comparing physical properties such as color, texture, and hardness.

- Recording data systematically using a worksheet or notebook.

- Explaining how different types of rocks form.

Background Information: Igneous, Sedimentary, Metamorphic Rocks

To identify rocks, children first need to know that there are three main types of rocks:

- Igneous Rock: These materials are produced when molten rock (called magma when underground and lava when above) cools and hardens. Igneous specimens like granite or pumice often have visible crystals.

- Sedimentary Rock: These rocks build up in layers over time. Small pieces of rock, along with sand, shells, and organic matter, are compacted over time to form sedimentary rock. You might even find a fossil hidden inside!

- Metamorphic Rock: These start as another kind of rock but are changed by intense heat and pressure deep underground. Metamorphic rocks are formed when the original minerals recrystallize into something new, like marble.

What Is the Rock Cycle?

The cycle is nature’s way of recycling. It describes how Earth’s materials change from one type of rock into another over time. A metamorphic specimen might melt into magma, cool into an igneous form, weather into sediment, and eventually compress into a sedimentary stone. This process takes millions of years, proving that the Earth is constantly, albeit slowly, reshaping itself.

Real Life Uses of Rocks

Rocks and minerals aren’t just for looking at; they are the building blocks of our civilization.

- Granite (Igneous): Used for kitchen countertops and monuments because of its extreme hardness.

- Limestone (Sedimentary): A key ingredient in cement and often contains calcium carbonate.

- Marble (Metamorphic): Favored by sculptors and architects for its beauty and ability to be polished.

Rock Identification Tests and Experiments

To categorize the collection, geologists use a series of standardized tests. These procedures help differentiate between a rock or mineral and determine the specific variety you have found.

Visual Observation Test – Color, Texture, Layers

Before picking up any tools, use a hand lens to look closely at the specimen.

- Texture: Is it grainy like sandpaper or smooth like glass?

- Layers: Does the sample look like it was built up in stacks? This often indicates a sedimentary origin.

- Crystals: Do you see shiny crystals? Large crystals form when magma cools slowly.

- Different Colours: Note the variety of hues, which can indicate which common minerals are present.

Hardness Scratch Test

The resistance of a surface to being scratched is a key clue. We use the Mohs Hardness Scale, which ranks minerals from 1 (softest) to 10 (hardest).

- Fingernail: If you can leave a mark with your fingernail, the sample is very soft (hardness around 2.5).

- Copper Coin: A penny can mark surfaces with a value of about 3.

- Steel Nail: If a fingernail and coin fail, try a steel nail (Hardness ~5.5).

Density and Buoyancy Test

Density measures how much mass is packed into a space.

- The Float Test: Most stones sink, but pumice is an igneous variety so full of air bubbles that it actually floats!

- Displacement: You can measure density by seeing how much water a sample displaces in a measuring cup.

Permeability Test – Water Absorption

Some sedimentary types are porous, meaning they have tiny holes that can soak up liquid. Dropping a little water on the surface and watching if it disappears can help you categorize materials like sandstone.

Acid Reaction Test

This is a favorite for kids of all ages. If you drop a little vinegar (a weak acid) on a specimen containing calcium carbonate (like limestone or marble), it will fizz and bubble! This reaction is a reliable way to identify rocks and minerals that contain calcium carbonate.

Extra Challenge Rock Problems

- The Mystery Light-Weight: An object that is grey, full of holes, and feels lighter than it looks. (Hint: It’s pumice).

- The Layered Mystery: A specimen that breaks into thin, flat sheets. (Hint: It could be slate, a metamorphic type).

- The Sparkling Giant: A heavy mass with large, pink and white crystals. (Hint: Likely granite).

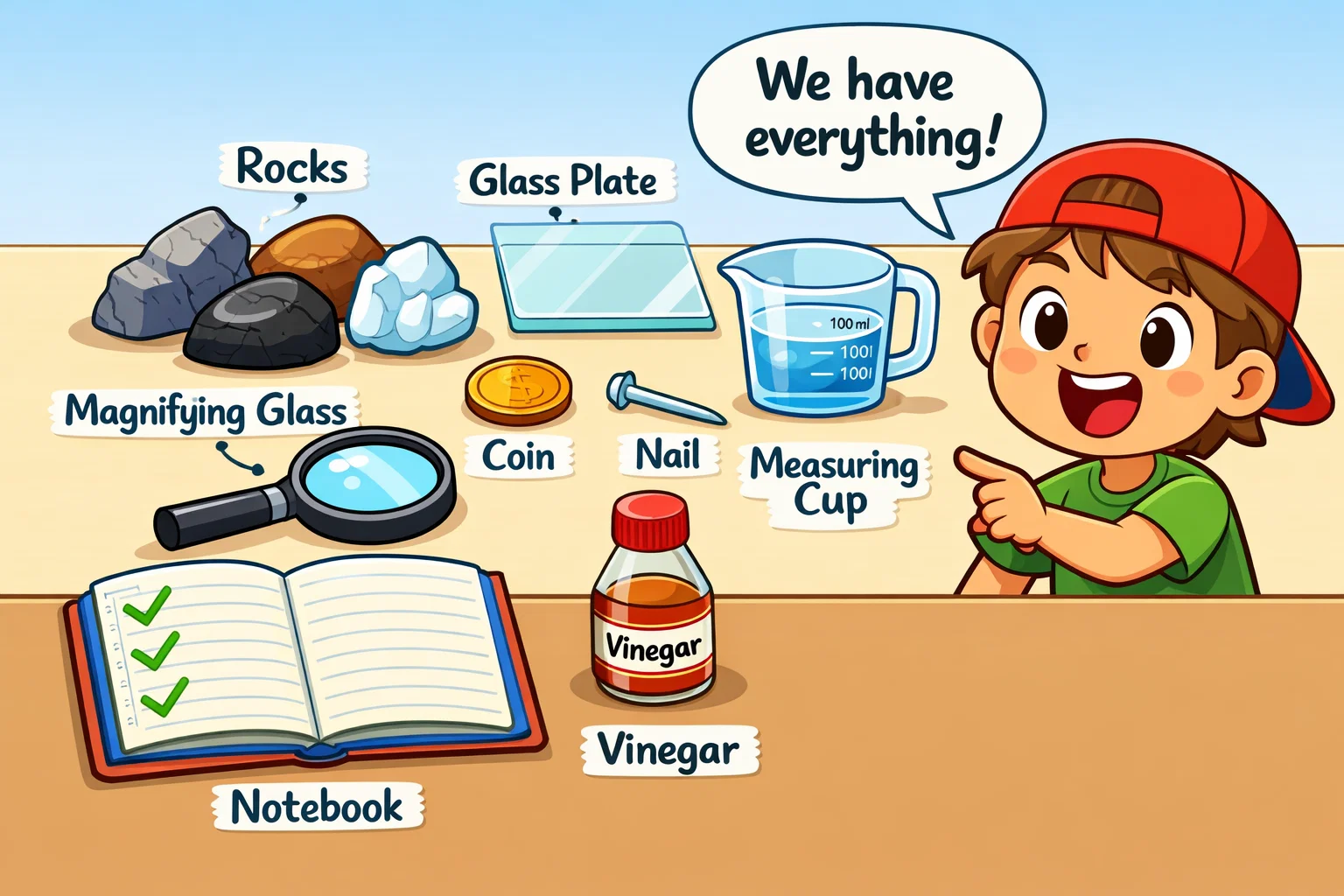

Supplies and Materials for Experiments

| Category | Items Needed |

| Basic Lab Kit | Samples, hand lens, notebook, pencils, ruler |

| Hardness Kit | Fingernail, copper penny, steel nail, glass plate (with adult supervision) |

| Fluid Tests | Vinegar, eyedropper, measuring cup, water, clear bowl |

| Recording | Printable rock identification worksheet, crayons for rubbings |

Step-by-Step Rock Identification Activity

Activity Setup

Find a well-lit workspace. Cover the area with newspaper or a plastic cloth, as some rocks contain dust or may crumble during testing. Ensure you have your worksheet ready to record your data.

Method and Testing Order

- Observation: Use the hand lens to check for fossil fragments or different colours.

- Scratch Test: Start with your fingernail and move up to the steel nail to determine hardness.

- Water Test: Check for permeability and buoyancy.

- Acid Test: Apply a drop of vinegar to see if the stone fizzes.

Recording Results

Create a table in your notebook. Write down the sample number, its color, whether it scratched, and if it reacted to acid. Recording “No reaction” is just as important as recording a “Fizz!”

Drawing Conclusions

Compare your results to a geology guidebook. If your find has layers and contains a fossil, it is almost certainly sedimentary. If it is very hard and has interlocking crystals, it is likely an igneous or metamorphic specimen.

Rock Activities for Kids – Extended Learning

Make Your Own Rocks Experiment

You can simulate how sedimentary rocks are formed by mixing sand, small pebbles, and a little glue or plaster of Paris. Press them into a cup and let them dry. You’ve just created a “clastic” model!

Rock Cycle Edible Model

This is one of the most popular science projects.

- Sedimentary Stage: Layer different colors of grated chocolate (the sediment).

- Metamorphic Stage: Apply heat and pressure by squeezing the chocolate in your warm hands (wrapped in foil).

- Igneous Stage: Melt the chocolate until it is hot enough to melt into molten liquid, then let it cool.

Man-Made Rocks Exploration

Discuss how humans make “stones” like concrete or bricks. Are they the same as natural rocks and minerals? (Hint: They are man-made materials that use natural ingredients such as limestone).

Rock School Challenge

Ask your child to create a mini-museum. They can group their collection in order of hardness or by type, creating labels for each.

How the Hardness Scale Works

The Mohs Hardness Scale was developed by Friedrich Mohs in 1812. It is a qualitative scale that characterizes the scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of a harder material to scratch a softer one.

Mohs Hardness Scale Explained

- Talc (softest – can be scratched easily with a fingernail)

- Gypsum (Can be scratched by a fingernail)

- Calcite (Fizzes with acid)

- Fluorite

- Apatite

- Orthoclase

- Quartz (Very common, very hard)

- Topaz

- Corundum (Rubies and Sapphires)

- Diamond (Hardest natural substance)

Matching Rocks to Hardness Levels

- Limestone: Typically around 3–4 on the scale, depending on its composition.

- Granite: Contains quartz and feldspar, usually 6-7.

- Soapstone: Very soft, often a 1 or 2.

Why Hardness Matters

Hardness determines how a material withstands the elements. Softer rock erodes quickly, forming valleys, while harder metamorphic and igneous formations often form the peaks of mountains.

Outcomes of Rock Identification Experiments

Participating in these science experiments provides more than just facts about the Earth.

- STEM Skills Development: Kids practice the scientific method—forming a hypothesis and testing it.

- Geography Connection: Understanding how Earth’s crust is made of different minerals helps kids understand why landscapes look different across the globe.

- Problem-Solving: If a test is inconclusive, children must think analytically to determine a different way to identify their samples.

Rock Identification Questions and Challenges

Example Rock Identification Questions

- “If a specimen fizzes when vinegar is applied to it, what mineral does it likely contain?” (Answer: Calcium carbonate).

- “If you find a sample near a volcano that is dark and has tiny holes, is it igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic?” (Answer: Igneous).

Rock Mystery Scenarios

- Scenario A: You find a stone with a shell fossil inside. It is easily scratched by a penny. What is it? (Sedimentary / Limestone).

- Scenario B: You find a green, shiny item that your steel nail cannot scratch. (Igneous / Jadeite or Quartz-based).

Advanced Rock Investigation Task

Go on a “Geology Walk” in your local park. Try to categorize the materials used in the pavement, the walls, and the natural outcrops. Are they native to your area or were they brought in by humans?

More Science Experiments for Kids

- Fossil Dig Activity: Bury plastic dinosaurs in plaster of Paris and let kids “excavate” them to learn about how fossils are preserved.

- Volcano Eruption Experiment: Use baking soda and vinegar to simulate magma escaping a volcano, demonstrating how pressure can cause gas release, similar to volcanic eruptions.

- Rainbow in a Jar: A great way to visualize density using different liquids like honey, water, and oil.

Deepening the Geological Knowledge: The Science of Earth

To truly appreciate the treasures under our feet, we must consider the vast scales of time and the incredible forces at play within the planet’s interior. Every pebble tells a story of tectonic plates shifting, mountains rising, and oceans retreating. When children handle a specimen, they aren’t just holding a piece of stone; they are holding a fragment of Earth’s history.

The Role of Plate Tectonics

The crust of our world is divided into massive plates that glide atop the mantle. Where these plates collide, the resulting intensity can transform sedimentary rocks such as shale into metamorphic rocks like slate or schist. This is the heart of the metamorphic process. Conversely, where plates pull apart, fiery liquid emerges from deep within, cooling into the solid foundations of the continents. Understanding this macro-perspective gives students a much broader context for why certain materials are found in specific regions.

Weathering and Erosion: Nature’s Sculptors

While subterranean forces create new materials, surface forces constantly break them down. Wind, rain, and ice act like sandpaper, wearing down the tallest peaks into tiny grains of sand and silt. This debris then travels through rivers and streams, eventually settling in quiet basins to become the next generation of sedimentary layers. Watching this cycle helps learners realize that the Earth is a dynamic system that is constantly changing.

Mineralogy: The Chemistry of the Ground

Each specimen is composed of specific chemical elements. For example, quartz is made of silicon and oxygen, while the fizzing reaction in some stones is caused by the presence of carbon. By exploring these chemical signatures, students can begin to link their finds to the periodic table, bridge the gap between geology and chemistry, and develop a more nuanced understanding of how matter is organized in the universe.