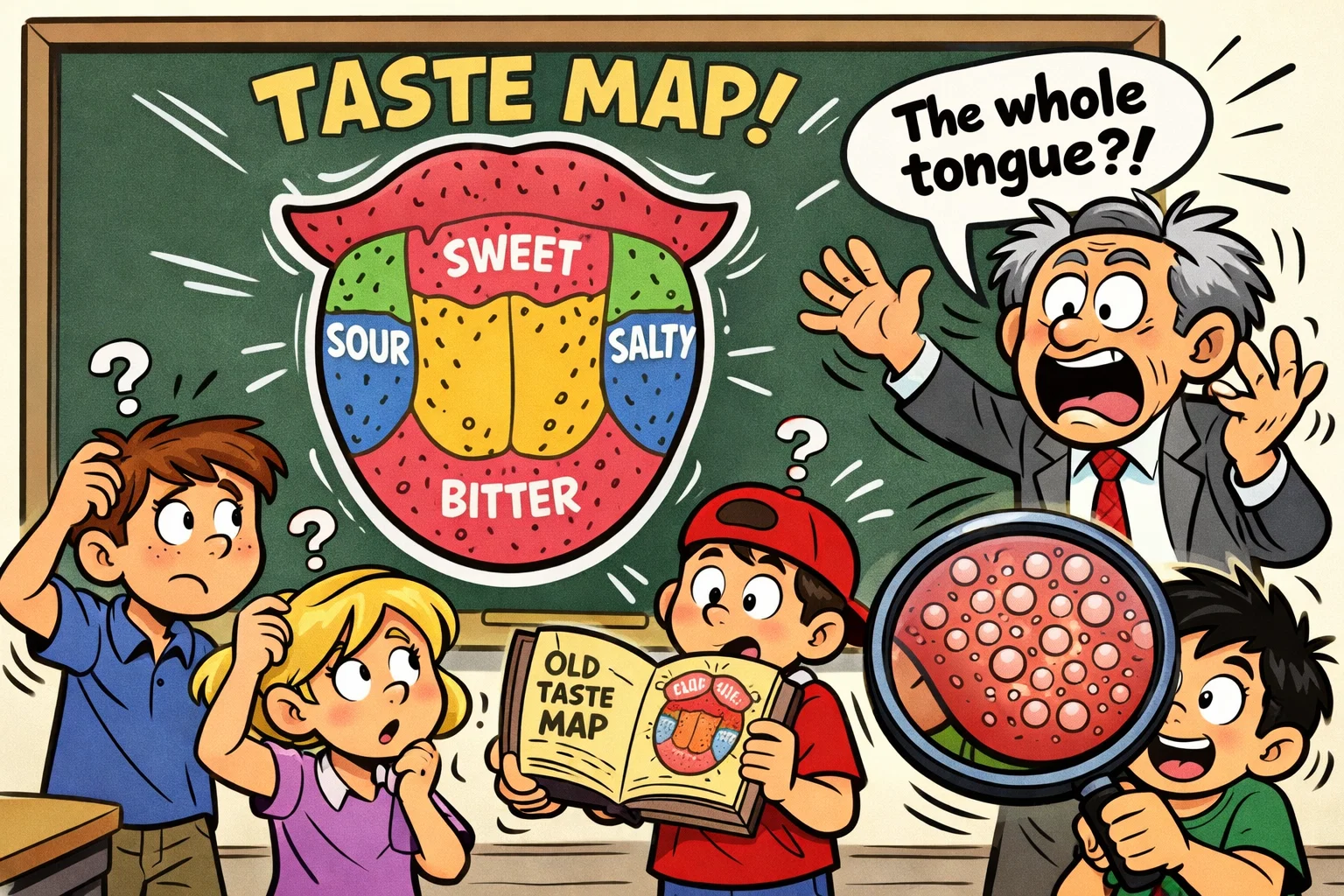

Have you ever opened a textbook and seen a colorful diagram of a tongue divided into neat, specific zones? For generations, students were taught that the tip of the tongue was exclusively for sweetness, sour sensations were believed to be detected on the sides, while bitter sensations were thought to be detected at the back, and salty and sour sensations lived in their own isolated patches. While this mapping looks organized and easy to memorize, modern anatomy and physiology tell a much more exciting story. It turns out that this famous map of the tongue is actually a myth that has persisted in the classroom for over a century, misleading even the most curious young scientists.

In this comprehensive guide, the fascinating world of sensation and perception is explored to become “myth-busting” experts. This guide explores how receptor cells actually work, why that old graph stuck around for so long in schools, and how you can perform a simple, hands-on experiment at home or in a lab to prove that the human body is much more complex than those old drawings suggest. By the end of this activity, students learn how sensory organs called taste buds work together to create the flavors of your favorite foods.

Taste Map Myth Explained

The idea of fixed taste zones is one of the most persistent misconceptions in basic science. For decades, it was widely believed that different parts of the tongue were exclusively responsible for perceiving certain tastes. This concept suggested that if you placed a drop of lemon juice on the “sweet zone,” you wouldn’t be able to tell it was sour. However, anyone who has ever eaten a meal knows this isn’t true. If a lollipop touches the back of the mouth and still tastes sweet and still finds it sugary, you’ve already started to debunk this idea using your own sensory experience!

Origin of tongue taste map

The confusion actually began over a century ago. In 1901, a German scientist, David P. Hänig published research on the sensitivity of different regions of the mouth. He was looking for the threshold at which people could first detect a stimulus. He found that some areas were slightly more sensitive to certain inputs than others, but his results were very subtle.

Later, in the 1940s, the psychologist Edwin Boring took this data and created a graph that simplified the findings. Unfortunately, this mapping was misinterpreted, making those tiny differences look like strict, physical boundaries. This led to the widespread belief that you could only feel sour at the sides or bitter at the back, a mistake that was eventually printed in many science textbooks worldwide.

Why myth became popular in classrooms

Teachers and publishers loved the taste map because it offered a clear, visual way to explain sensory systems to children. It looked great on posters and was easy to include in a lab manual. Even though chemosensory scientists knew the truth by the 1970s, the visual of a tongue with different zones was so simple that it stayed in the curriculum for decades. It is much easier to test a student on a “map” than it is to explain the complex physiology of different taste receptors working all at once.

Common misconceptions kids believe

Because of these old posters, most children (and many adults!) still believe in the four-zone model. They often approach a science experiment expecting these specific results:

- Sweetness: Believed to be sensed only at the front of the tongue.

- Salty: Thought to be recognized only on the front edges of the tongue.

- Sour: Believed to be sour on the sides or sour at the sides only.

- Bitter: Assumed to be bitter at the back with no other area sensitive to tastes.

- Middle: Often thought to be a “dead zone” with no perception at all.

How Taste Really Works

To understand the truth, we must look at the tiny sensory organs called taste buds. Your tongue is covered in small bumps called papillae, which house these vital sensors. Each papilla can contain multiple taste buds, and each bud is packed with individual taste cells that act as receptors.

Taste buds location on tongue

Contrary to the old-fashioned diagram, taste buds are found across the entire surface of the tongue, the roof of the mouth, and even the throat. Every area contains different taste receptors that can pick up these tastes regardless of where the food lands. While it is true that the tip of the tongue is very sensitive to certain tastes, it is not the only place that can detect them.

Five basic taste types

While the old map only showed four profiles, scientists now recognize a fifth. We have receptors for sweet, salty, sour, bitter and umami. Umami is a savory taste found in foods like parmesan cheese, mushrooms, or soy sauce. It provides a rich, savory flavor that balances other tastes.

Role of brain in taste perception

The tongue is the collector of information, but the brain is the translator. When a receptor catches a molecule, it sends a signal through two cranial nerves, including the chorda tympani. These signals travel to the brain to create the actual perception of what you are eating. Modern sensory science shows that the brain processes taste as a whole-mouth experience rather than isolated zones.

Taste Buds Experiment for Kids

Goal of taste map myth test

The objective of this hands-on activity is to determine if different sections of the mouth are truly limited to one sensation. We want to see if we can detect different taste profiles in “wrong” areas according to the myth.

Materials needed for experiment

To run a proper lab at home or in the classroom, you will need:

- Sweet Solution: Sugar dissolved in water to test for sweetness.

- Salty Solution: Salt dissolved in water.

- Sour Solution: Lemon juice (to test sour at the sides).

- Bitter Solution: Unsweetened cocoa or tonic water (to test bitter compounds).

- Umami: A tiny bit of broth or diluted soy sauce.

- Tools: Clean cotton swabs, paper cups, and fresh water.

- Data Collection: A tongue drawing or a graph to record where you feel each taste.

Safety tips for children

Always ensure adult supervision during this science experiment. Use a new cotton swab for every single drip to prevent mixing flavors or spreading germs. If a child finds a flavor like bitter too strong, they should have plenty of water nearby to rinse their mouth and return to a resting state.

Step-by-Step Taste Map Myth Test

Preparation before testing

Prepare your solutions in separate cups and label them clearly. Make sure the child understands the scientific method: we are making a prediction (the tongue map is true) and then testing it to see if our data supports or debunks it.

Testing different tongue areas

- Dip a clean swab into the sweetness solution.

- Touch the swab to the front of the tongue, then the edges of the tongue, and finally the back.

- Ask: “Can you detect the sugar in all these different regions of the tongue?”

- Rinse with water and wait one minute for the mouth to return to its normal state.

- Repeat this process for sour and bitter solutions, as well as the savory taste of umami.

Recording results on taste chart

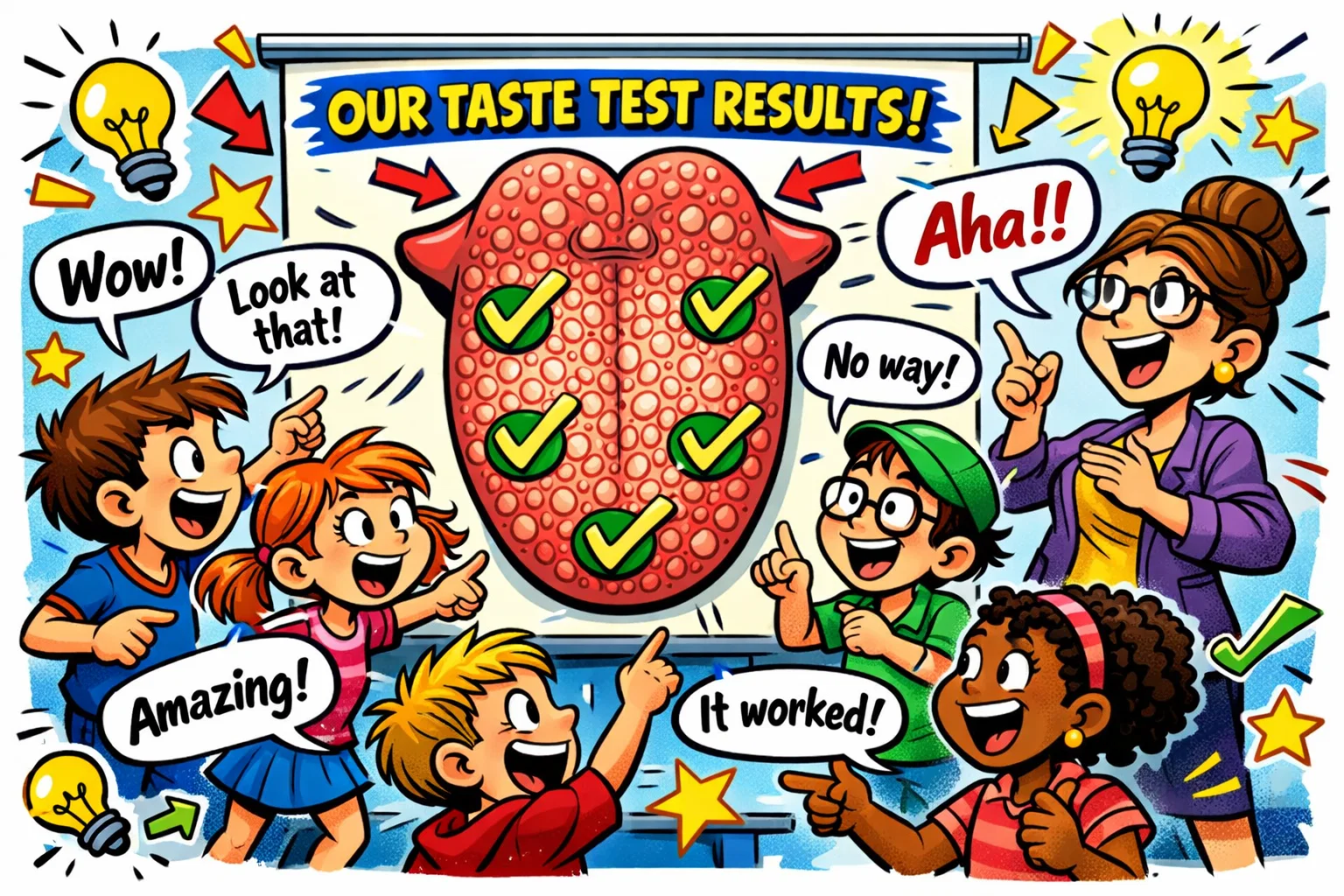

Have the child mark a “Yes” or “No” on their diagram for each area. They will quickly see that they are perceiving certain tastes in every location they test, which directly contradicts the 1940s map of the tongue.

Experiment Results Explained

What kids usually notice

Most children will find that they could taste the salt and sugar even in the “bitter zone” at the back. While some might say the sides and bitter area feels more intense, they often notice that the front of the tongue is also sensitive to tastes that aren’t just sweet.

Why results debunk taste map

These results show that receptors that pick up flavors are spread out. This proves that the anatomy of the mouth doesn’t have “borders.” It is a unified sensory system where different taste receptors work together.

Why taste strength may vary

It is true that the tip and edges have a high density of taste buds, which might make them slightly more sensitive to certain inputs. However, being “more sensitive” is not the same as being the “only area” that works.

Science Behind Taste Perception

Taste receptors and nerve signals

Each of your sensory organs called taste buds is a complex machine. They use receptor cells to catch food molecules. Just as your heart reacts to vigorous exercise, your mouth reacts to chemical changes in food.

Smell and taste connection

A huge part of flavour is actually smell. If you anaesthetise your sense of smell by pinching your nose, a lemon might just taste “sour” without the “citrus” perception.

Why bitterness feels stronger

We are naturally more sensitive to certain bitter compounds because, in nature, bitter often means “poison.” Our physiology is designed to detect these to keep us safe.

Educational Benefits for Kids

- Critical Thinking: Children learn that even a textbook can be outdated and that they should use the scientific method to find the truth.

- Hands-on Learning: Using different taste solutions makes biology fun and memorable.

- Anatomy Knowledge: Kids learn about two cranial nerves, the chorda tympani, and how the brain processes sensory data.

Classroom and Home Activity Ideas

Group classroom experiment

In a classroom setting, you can collect data from 30 different students. A wide range of results is usually observed in how people sense bitter and umami. This shows that individual taste is unique!

Science fair project variation

A great variation is to test how exercise affects our perception. Does your heart rate during exercise change how you sense sweetness? You can measure heart rate in beats per minute before and after jumping jacks to see if there is a link.

Follow-up discussion questions

- Why did the German scientist David Hanig’s work get misunderstood?

- How does the return to a resting rate of the heart compare to the time it takes for a flavour to fade?

- Why is umami called a savory taste?

Related Science Experiments for Kids: The Heart

While we are discussing the human body and physiology, let’s look at the cardiovascular system. The way the heart pumps blood through the body is just as fascinating as how we detect food!

Heart Rate and Exercise

You can measure heart rate by finding the radial pulse on the wrist or the carotid pulse on the neck.

- Resting Rate: Count the number of beats for one minute while sedentary.

- Exercise: Perform jumping jacks or other vigorous aerobic movement for five minutes.

- Recovery: See how long it takes for the heart to return to a resting state.

| Activity Level | Heart Rate (BPM) | Physiology Note |

| Sedentary | 60-80 | Normal resting pulse |

| Moderate Exercise | 100-120 | Heart pumps blood to muscles |

| Vigorous (Jumping Jacks) | 140+ | High gas exchange needed |

Heart Recovery Period

The time it takes for your heart to return to its normal rate is called the recovery period. A fit athlete will have a very fast heart recovery. This is because their cardiovascular system is efficient at gas exchange and can remove carbon dioxide quickly. If you exercise regularly, your heart rate would likely drop back to normal much faster than someone who is sedentary.

Share Experiment Results

Sharing results with classmates

Create a large diagram of the “Real Tongue Map” based on your lab results. You can even include a graph showing how your heart rate in beats per minute changed during the activity.

Sharing experiment online

Post your findings to show other kids that the textbook map is a myth. Use photos of your different taste solutions and your sensation and perception charts.

Related Content

- Human Body Systems: How the cardiovascular and sensory systems work together.

- Myth-Busting Science: Why we should always test individual taste and old theories.

- Healthy Habits: How exercise regularly prevents heart disease and keeps your anatomy strong.